A Sterling Review Investigative Analysis

China’s edge in electric vehicles (EVs) isn’t just cheaper labor or subsidies; it’s a vertically integrated manufacturing machine built on high robot density, “lights-out” (dark) factory automation, battery innovation, and—crucially—an education/upskilling system tuned to mass technical deployment. This synergistic system creates a self-reinforcing flywheel that drives cost reduction, quality control, and rapid iteration unparalleled in global automotive history.

Contrast this with the United States, where EV technology leadership remains strong in software, semiconductors, and fundamental research, but scaling capability is severely constrained. This constraint manifests in fragmented supply chains, significantly lower robot density in manufacturing, and a structurally narrower and slower-to-adapt technical workforce pipeline. The systemic gap suggests that tariffs alone cannot restore competitiveness; they only buy time for the U.S. to address foundational deficits in industrial automation and human capital formation.

I. Lede: The Lights-Out Engine of Global Manufacturing

A subterranean hum replaces the clamor of human activity within the walls of a cutting-edge battery assembly facility outside Hefei. Here, under the dim, energy-efficient glow of operational monitors—a true “dark factory” module—thousands of laser-guided Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) shuttle structural battery casings between automated welding cells. Six-axis industrial robots perform micron-level adhesive dispensing and complex, thermal-sensitive welding of Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) cells into structural chassis elements. There are no assembly line workers, only highly skilled technicians monitoring diagnostics from a control room. This hyper-automated environment guarantees the consistency and quality control necessary for safety-critical components in modern electric vehicles.

This scene, replicated across dozens of China’s new energy vehicle (NEV) production clusters, is the hidden foundation of the country’s accelerating global automotive dominance. The structural integration of advanced automation, perfected battery technology, and a massive, technically aligned workforce has created an industrial engine that operates on a different plane of efficiency and scale than its Western counterparts. China is not merely making EVs; it is defining the automated, integrated architecture of the next generation of global manufacturing. Understanding this systems-level advantage—which goes far beyond subsidies and low-cost labor—is critical for assessing the geopolitical stakes facing the United States and Europe.

II. The Automation Gap: Quantifying the Manufacturing Chasm

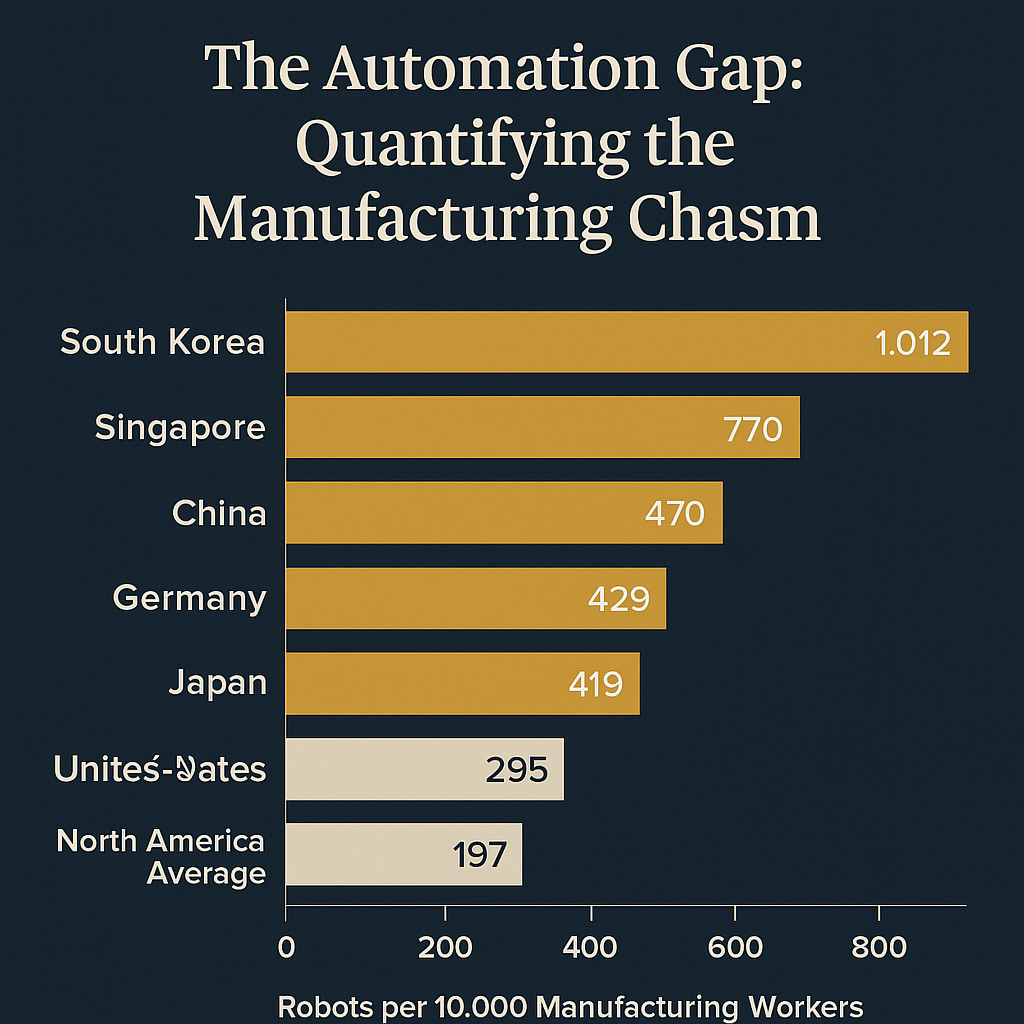

The bedrock of China’s production superiority is its relentless capital investment in industrial automation, quantified starkly by metrics for robot density and installation growth. The global average robot density reached a record 162 units per 10,000 employees in 2023, reflecting a doubling in robot adoption over the past seven years.1 China has led this global transformation.

A. The Density Deficit: China’s Accelerator Strategy

China’s commitment to automation surpasses nearly all major industrialized rivals. The International Federation of Robotics (IFR) reports that China achieved a robot density of approximately 470 units per 10,000 manufacturing workers in 2023, positioning it as the world’s third most automated nation, behind only South Korea and Singapore. By stark contrast, the United States stood at approximately 295 units per 10,000 manufacturing workers in 2023.2

The disparity between China and the U.S. is nearly 60%, signaling a profound chasm in production efficiency and capital intensity. Furthermore, while the U.S. is increasing its robot adoption, its pace is insufficient to maintain competitive standing, resulting in a drop in the global ranking from tenth in 2022 to outside the top ten in 2023.2 This high fixed capital investment, reflected in China’s 470 density, translates directly into a structural cost advantage based on lower operational expenditure and higher throughput per unit of labor. This advantage is far more durable against economic volatility or wage increases than simple reliance on cheaper labor costs.

B. Installation Momentum and Geographic Concentration

The momentum behind China’s automation drive ensures this gap will continue to widen. Annual installation data confirms that Asia remains the central hub for manufacturing automation globally, leveraging the newest generations of industrial hardware. In 2023, Asia accounted for an overwhelming 70% of all newly deployed robots globally, while Europe accounted for 17%, and the Americas accounted for only 10%.3 China remains, by far, the world’s largest individual market for industrial robots, with annual installations exceeding 290,000 units in 2022.4

This concentration of capital investment and installation volume ensures that Chinese manufacturers have the latest hardware, sophisticated integrators, and the fastest accumulation of operational data and maintenance expertise. This rapid learning curve is a critical element for mastering the complex, high-tolerance production demands of advanced EV architectures.

C. Case Box: The Operational Reality of “Lights-Out”

The term “lights-out” or “dark factory” often functions as an industrial benchmark, signifying highly advanced, fully automated manufacturing. While the complete elimination of human intervention from raw material input to final vehicle rollout is rare, the principle is strategically real and most critically applied to areas demanding extreme precision and quality consistency.

High-profile case studies, such as the widely referenced examples in Dongguan or the battery facilities in Hefei, illustrate modular automation in key manufacturing stages. In the EV sector, this capability is essential for tasks like electrode coating, cell stacking, and structural battery welding. The complexity of modern Cell-to-Pack (CTP) designs (discussed in Section IV) requires sub-millimeter precision in assembly and stringent thermal management controls. This high-automation approach overcomes the quality variability associated with complex, high-voltage component assembly, cementing consistency across millions of units—effectively making the automation gap a technical feasibility gap for producing high-integration EV designs in the U.S. at competitive prices.

III. EV Scale and Export Muscle: The Global Auto Workshop

The speed at which China has utilized its automated capacity to transition from a primarily domestic market focus to the world’s leading automobile exporter demonstrates a profound and definitive shift in global industrial power.

A. Quantifying China’s Production and Export Dominance

China’s industrial engine is operating at a scale that is setting the global pace. In 2023, Chinese carmakers produced more than half of all electric cars sold worldwide, a remarkable figure given their relatively small share of global internal combustion engine (ICE) sales.5 This is supported by an enormous domestic market where the electric car share is projected to reach up to 45% in 2024, vastly outpacing the U.S. market share of just over 11%.5

Leveraging this domestic scale, China has secured its place as the world’s largest auto exporter. IEA data for 2024 projections confirms China’s critical role, estimating that China will account for approximately 40% of global EV exports, translating to an estimated 1.2 to 1.25 million EVs exported globally.5 This expansion is accelerating: exports of New Energy Vehicles (NEVs) experienced a 100% year-on-year jump in a single representative month in 2023.6

The following visual clarifies the dominant position of China in the global EV trade volume:

EV Exports by Origin (Approximate Share of Global Total, 2024)

| Origin | Approximate Share | Approximate Volume (Millions) |

| China | 40% | 1.25M |

| EU | ~25% | >0.80M |

| Asia-Pacific (ex-China) | ~20% | ~0.64M |

| Rest of World | ~15% | Remainder |

B. Domestic Pressure as the Engine of Global Expansion

The intense, hyper-competitive nature of the Chinese EV market is the primary catalyst driving global expansion. Cut-throat competition among dozens of domestic and international automakers (including BYD, Geely, Nio, and Tesla) forces extraordinary efficiency and cost-cutting within China. This domestic pressure is existential, driving Chinese automakers, such as BYD and Great Wall, to expand aggressively overseas to utilize built-up factory capacity and maintain necessary production volumes.7

This hyper-competition, while ensuring low prices for consumers, has created a situation of market overcapacity and severely compressed profit margins. As evidenced by market leader BYD, net profit fell nearly 30% year-over-year in the second quarter of 2025, even as revenue continued to grow.8 This decline signals that companies are sacrificing margin for volume, underscoring that access to foreign markets is not merely opportunistic but essential for utilizing this overcapacity and ensuring corporate viability amid domestic price wars. This strategic requirement makes the Chinese EV sector highly vulnerable to escalating trade and tariff frictions.9

The strategic importance of this export wave extends beyond volume; the mass export of 1.25 million EVs represents the globalization of proprietary, indigenously designed intellectual property—specifically battery architectures and highly integrated e-platforms. China is beginning to define the new technical standards for efficiency, integration, and cost structure globally, a clear erosion of the century-old technical dominance held by Western original equipment manufacturers (OEMs).

IV. Battery & Platform Innovation: The Technical Architecture of Advantage

China’s technical competitive advantage is characterized by rapid, pragmatic integration of mature technology (like Lithium Iron Phosphate, or LFP) with next-generation, high-efficiency systems (800V and Silicon Carbide, or SiC), enabling superior cost structures and performance parity with global rivals.

A. Battery Structural Integration: The Cost and Safety Nexus

Key Chinese battery manufacturers have pioneered structural integration techniques that maximize efficiency and safety while reducing complexity and cost.

- BYD Blade Battery (LFP): Manufactured by BYD’s FinDreams Battery subsidiary, the Blade battery leverages LFP chemistry for its inherent safety advantages: slow heat generation, low heat release, and non-oxygen release properties.10 The fundamental innovation is the Cell-to-Pack (CTP) architecture, where long, thin cells are placed directly into the pack structure, increasing space utilization by over 50% compared to traditional block batteries.11 This design is further leveraged as a structural component, with each cell serving as a beam to enhance the overall rigidity of the vehicle body.12

- CATL Qilin Battery: Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL) has pushed CTP integration further. The Qilin design focuses on maximizing volumetric efficiency across various chemistries. For high energy density cells, such as nickel manganese cobalt (NMC), the Qilin technology aims for an energy density of up to 330 Wh/kg.13 This allows Chinese OEMs to deliver competitive ultra-long-range models while benefiting from the integration advantages of the CTP approach.

B. Platform Standardization and High-Integration Architecture

Beyond the cell level, Chinese automakers are rapidly standardizing high-voltage, high-efficiency vehicle architectures. The adoption of 800V architectures paired with advanced Silicon Carbide (SiC) inverters is rapidly becoming standard across multiple segments.14 SiC improves efficiency and thermal performance, minimizing energy loss during operation. This architecture is crucial for supporting ultra-fast DC charging and includes integrated features, such as DC boost functions, which allow 800V vehicles to maintain optimized charging speeds even when connected to legacy 400V charging infrastructure.14

The clearest example of this integrated strategy is the BYD e-Platform 3.0. This architecture embodies vertical integration by featuring the world’s first mass-produced 8-in-1 electric powertrain as standard, consolidating components like the motor, transmission, and inverter into a single, high-efficiency unit.12 This integration reduces component count, simplifies assembly, and minimizes energy transfer losses, resulting in an overall system efficiency of up to 89%.12 The platform also features an intelligent thermal management system that reuses residual heat, increasing thermal efficiency by up to 20% in cold weather.16

This table details the technical specifications driving the current advantage:

Advanced EV Component and Platform Comparison

| Component/Technology | Manufacturer | Energy Density (Wh/kg) | Integration Approach | Core Advantage Claim |

| BYD Blade Battery (LFP) | BYD (FinDreams) | N/A (LFP Chemistry) | Cell-to-Pack (CTP) / Structural | Enhanced safety (Nail Penetration Test), increased space utilization (>50%), structural rigidity [10, 11] |

| CATL Qilin Battery (NMC/LFP) | CATL | Up to 330 Wh/kg (NMC) | Cell-to-Pack (CTP) / Structural | Ultra-long range, high volume utilization, fast charging (4C) 13 |

| E-Platform 3.0 | BYD | N/A | High Integration (8-in-1 Powertrain) | System efficiency up to 89%, intelligent thermal management, integrated SiC modules [12, 16] |

The strategic choice to standardize advanced, integrated platforms across various models allows Chinese manufacturers to maximize the scale of component production, ensuring that the cost curve declines faster than that of Western rivals who often rely on custom architectures. Furthermore, the E-Platform 3.0 is designed with an integrated domain-controlled architecture.12 This software-first approach allows for superior interactive efficiency and continuous over-the-air upgrades, positioning the vehicles as rapidly iterating technological devices—a critical element of modern vehicle competitiveness.

V. The Apple Effect: Industrial Learning at Scale

China’s rapid, successful transition to EV dominance is predicated on the institutional knowledge, supply chain resilience, and massive workforce capacity first developed while serving the global consumer electronics industry, with the partnership between Foxconn and Apple serving as the defining case study for industrial transfer.

A. The Transfer of Scale and Complexity Management

For decades, Taiwan-owned Foxconn served as the principal manufacturer for Apple products, establishing itself as the world’s largest electronics contractor.17 This established the capacity within China to manage global, multi-million-unit production runs under the highly stringent quality and logistical demands of a global technology leader. At its peak, Foxconn employed 1.4 million workers in China alone.17

The necessary industrial know-how for EVs transferred efficiently: expertise in precision tooling, high-volume production management, the assembly of multi-layered circuit boards, complex software integration, and the management of deep, reliable supplier networks (Tier 2 and Tier 3 component manufacturers) were readily repurposed. This learning process dramatically shortened the ramp-up time required for sophisticated battery module assembly and vehicle electronics integration, enabling Chinese automakers to bypass years of traditional automotive development cycles.

B. Labor Organization and Agility Caveats

The industrial framework built by large-scale contractors demonstrated an unparalleled ability to rapidly adjust volume based on market demand. Foxconn, for instance, showed the ability to mobilize between 150,000 and 200,000 workers during peak season at its Zhengzhou facility.18 This ability to mobilize a massive, flexible workforce translates directly to the rapid EV mass production ramp-ups seen today in major NEV clusters.

However, this rapid scaling capability is enabled by operational flexibility that often contravenes standard labor protections. China Labor Watch investigations have documented systemic labor violations, including reliance on dispatch workers exceeding the legal limit by five times (over 50% of the peak workforce) and mandatory excessive overtime (60–75 hours per week).17 While these practices enable rapid industrial scaling, they introduce clear ethical and geopolitical risks. The reality is that the Chinese industrial model leverages both forces—high automation (for precision and consistency in dark factories) and high human labor flexibility (for rapid volume adjustments)—to optimize for quality control and extreme market responsiveness.

Crucially, the enduring presence of this dense, highly efficient electronics and battery component supplier ecosystem in China creates powerful inertia. U.S. and European reshoring efforts face a massive hurdle in re-creating the dense cluster of Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers for specialized adhesives, high-precision electronic components, and thermal management systems that enable the high-integration architectures detailed in Section IV.

VI. The Education Flywheel: Fueling the Talent Pipeline

The long-term, decisive factor enabling China’s sustained technological and manufacturing advantage is its systematic, state-aligned investment in technical human capital, creating a self-reinforcing loop that feeds industrial automation and innovation.

A. The STEM PhD Gap: A Strategic Deficit

At the highest level of research and development, China has achieved quantitative supremacy. Analysis by Georgetown CSET shows that China surpassed the United States in the annual number of STEM PhD graduates in 2007.20

The projections for future output are even more striking. Based on current enrollment patterns, by 2025 China’s yearly STEM PhD graduates are expected to nearly double the total output of the United States. When the U.S. output is compared only against domestically enrolled students (excluding temporary international visa holders), China’s PhD output is projected to be more than three times as high.20

This growing deficit ensures that China has a massive, domestically secured talent pool necessary to staff its advanced R&D centers, program its automated dark factories, design new SiC power electronics, and lead fundamental research in battery chemistry. While the U.S. maintains a qualitative edge in certain top-tier research fields, China’s sheer quantitative output of skilled personnel provides the necessary technical mass to deploy and industrialize innovation at massive scale. The complexity and high density of robots (470 units per 10,000 workers) requires millions of highly trained human minds to commission, maintain, and optimize.

B. The Technical/Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Pipeline

China’s Technical/Vocational Education and Training (TVET) system provides the critical linkage between high-level research and practical industrial deployment. This system is structurally aligned to immediately meet industrial demand, integrating both foundational education and specific technical skills.22

The TVET pipeline is highly responsive to the rapid technological shifts demanded by the EV transition. Vocational institutions have rapidly updated their curricula to provide skills specific to the New Energy sector, deploying specialized equipment such as electric car drive motor trainers and fuel cell training equipment.23 This rapid curricular alignment ensures a continuous supply of mid-skill maintenance technicians, engineers, and programmers capable of installing, operating, and servicing advanced automation equipment and the complex 8-in-1 e-platforms found in modern EV production clusters (Shenzhen, Shanghai, Hefei).

This systematic approach stands in stark contrast to U.S. bottlenecks. The U.S. technical education and apprenticeship system remains fragmented and slower to adapt. Community college programs often lack the swift national funding or alignment necessary to pivot curricula quickly to meet the specialized demands of 800V architectures, advanced robotics integration, and high-voltage battery maintenance. Furthermore, the significant reliance on temporary international students for U.S. STEM PhD output makes the nation’s top-tier technical workforce supply vulnerable to fluctuations in immigration policy, while China’s talent base, being overwhelmingly domestic, is structurally more resilient and predictable.

VII. U.S. Position & Paths Forward: Rebuilding Industrial Resiliency

The structural competitive advantages China has built require the United States to implement policies that address fundamental deficits in automation, supply chain depth, and technical human capital, moving beyond merely targeted subsidies.

A. Assessing U.S. Strengths and Scaling Constraints

The U.S. retains fundamental technological leads that can be leveraged effectively: dominance in complex vehicle software stacks and autonomous driving R&D; strong foundational research and domestic manufacturing expansion in next-generation Silicon Carbide (SiC) devices, which are crucial for high-efficiency 800V systems 15; and unmatched top-tier academic research institutions.

However, the inability to convert these advantages into mass-market scale at competitive prices is constrained by three structural weaknesses: the persistent density deficit (295 robots per 10k workers vs. China’s 470); a shallow and fragmented domestic Tier 2/Tier 3 supplier base, which increases input costs and time-to-market for complex integrated parts; and a technical workforce pipeline that is slow to adapt to new EV manufacturing specializations.

B. Counterpoints and Risks for China

A balanced analysis requires acknowledging key structural risks facing the Chinese EV ecosystem:

- Overcapacity and Margin Compression: The intense domestic price war, driven by vast manufacturing overcapacity 9, is fiscally unsustainable for many participants. The experience of market leaders like BYD, where significant profit erosion was reported despite rising sales volume in 2025 8, confirms that the current competition level is pressuring overall financial stability and corporate viability.

- Geopolitical and Trade Friction: China’s aggressive export strategy is now triggering a comprehensive international policy backlash, including U.S. and EU tariff escalations and anti-subsidy investigations.9 These frictions directly threaten access to high-value foreign markets, potentially forcing a painful and costly consolidation period domestically.

- Quality Control and Trust: The extraordinary speed of China’s scale-up, combined with documented labor compliance issues 19, introduces latent risks regarding long-term vehicle quality consistency and consumer trust, particularly as Chinese brands attempt to transition from budget-friendly exports to premium offerings in global markets.

C. Three Actionable Levers for U.S. Policy

Strategic policy intervention must target the structural weaknesses identified, focusing on enabling systemic efficiency rather than temporary protection.

- Robot Adoption Incentives Tied to Domestic Content: The U.S. must implement targeted tax credits and fiscal incentives designed to accelerate the adoption of robotics and automation equipment, directly addressing the automation deficit.24 These incentives must be specifically tied to manufacturers who commit to meeting stringent domestic content requirements. This approach reduces the high upfront capital cost of automation and ensures that federal support translates directly into higher domestic throughput and efficiency, moving the country closer to competitive parity with automated nations.

- Modernized Technical Education & Apprenticeships (TVET 2.0): Policy must fund and mandate a structural overhaul of the U.S. technical education system, transforming it into a demand-driven model.22 Federal grants should be contingent on community colleges aligning curricula with advanced EV technologies (800V architectures, SiC power electronics, and advanced robotics programming). Federally backed, industry-led apprenticeship programs are essential to quickly develop the high-skill installation, maintenance, and technical workforce required to support large-scale automated factories, mirroring the operational effectiveness of the Chinese system.

- Battery Supply-Chain Acceleration and Know-How Transfer: Regulatory and permitting timelines for domestic battery material processing and specialized component manufacturing joint ventures (JVs) must be drastically streamlined to reduce scaling inertia. Policy should further leverage these JVs to facilitate the rapid acquisition of specialized know-how in advanced integration techniques (such as CTP/8-in-1 architectures) from established Asian partners, thereby accelerating the depth and efficiency of the domestic supply chain beyond simple final assembly.

VIII. Closer: The Systemic Differentiator

China’s competitive advantage in electric vehicles is not defined by any single breakthrough—not a single battery chemistry, not one subsidy, nor cheap labor—but by systemic, unified industrial execution. The seamless, self-reinforcing flow between massive capital investment (high robot density and dark factories), proprietary integrated platforms (Blade/Qilin CTP and 8-in-1 SiC powertrains), and a vast, technically aligned human capital engine (the Education Flywheel) creates an industrial structure that compounds advantage with every vehicle produced. The challenge for the United States, therefore, is not simply catching up on technology; it is replicating this complex, symbiotic system—a challenge that demands a strategic commitment to automation, education, and industrial speed that transcends traditional policy boundaries.

Works cited

- Global Robot Density in Factories Doubled in Seven Years, accessed October 31, 2025, https://ifr.org/ifr-press-releases/global-robot-density-in-factories-doubled-in-seven-years

- In just seven years, the global robot density in factories has doubled, IFR finds, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.therobotreport.com/in-just-seven-years-global-robot-density-factories-has-doubled-ifr-finds/

- Record of 4 Million Robots in Factories Worldwide – International Federation of Robotics, accessed October 31, 2025, https://ifr.org/news/record-of-4-million-robots-working-in-factories-worldwide/

- World Robotics 2023 Report: Asia ahead of Europe and the Americas, accessed October 31, 2025, https://ifr.org/ifr-press-releases/news/world-robotics-2023-report-asia-ahead-of-europe-and-the-americas

- Executive summary – Global EV Outlook 2024 – Analysis – IEA, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/executive-summary

- China’s exports of electric vehicles doubled in September as competition at home intensifies, accessed October 31, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/china-auto-sales-ev-tariffs-49620d1bbcc56723d4bd4c9983829785

- China’s fast-growing EV makers pursuing varied routes to global expansion – AP News, accessed October 31, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/china-ev-tariffs-geely-byd-51b3c0040bbe25c9d5636d70a4011e2e

- 3 Major Risks Investors Should Watch at BYD | The Motley Fool, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.fool.com/investing/2025/10/30/3-major-risks-investors-should-watch-at-byd/

- Beyond Overcapacity: Chinese-Style Modernization and the Clash of Economic Models – Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), accessed October 31, 2025, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/MERICS%20Report%20Overcapacities_2025%20final.pdf

- BYD Blade Battery | BYD Europe, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.byd.com/eu/technology/byd-blade-battery

- BYD Blade battery – Wikipedia, accessed October 31, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BYD_Blade_battery

- e-Platform 3.0 | BYD Europe, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.byd.com/eu/technology/byd-e-platform-3

- Innovative Technology – CATL, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.catl.com/en/research/technology/

- New SiC-based inverter subassembly targets 800V+ EV architectures, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.evengineeringonline.com/new-sic-based-inverter-subassembly-targets-800v-ev-architectures/

- Add Miles and Years of Performance to Your Next 800V EV Traction Inverter Platform, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.nxp.com/company/about-nxp/smarter-world-blog/BL-800V-EV-TRACTION-INVERTER-PLATFORM

- Why is BYD’s e-Platform 3.0 so special?, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.byd.com/eu/blog/Why-is-BYDs-e-Platform-3-0-so-special

- The politics of global production: Apple, Foxconn and Chinas new working class, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.responsibleglobalvaluechains.org/images/PDF/Jenny-Chan_The-politics-of-global-production.pdf

- China Labor Watch Exposes Labor Rights Violations at Foxconn iPhone 17 Factory, accessed October 31, 2025, https://goodelectronics.org/china-labor-watch-exposes-labor-rights-violations-at-foxconn-iphone-17-factory/

- China Labor Watch Raises Serious Concerns Over Alleged Labor Violations at Foxconn iPhone 17 Factory, accessed October 31, 2025, https://chinalaborwatch.org/china-labor-watch-raises-serious-concerns-over-alleged-labor-violations-at-foxconn-iphone-17-factory/

- China is Fast Outpacing U.S. STEM PhD Growth – Center for Security and Emerging Technology, accessed October 31, 2025, https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/China-is-Fast-Outpacing-U.S.-STEM-PhD-Growth.pdf

- The Global Distribution of STEM Graduates: Which Countries Lead the Way? | Center for Security and Emerging Technology – CSET, accessed October 31, 2025, https://cset.georgetown.edu/article/the-global-distribution-of-stem-graduates-which-countries-lead-the-way/

- Technical and Vocational Education and Training: Lessons from China – World Bank, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/10/30/technical-and-vocational-education-and-training-lessons-from-china

- Guangzhou Guangtong Educational Equipment Co., Ltd: China educational equipment , automotive training equipment, electric vehicle training equipment Manufacturer, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.gteecn.com/

- Memos to the National Robotics Strategy – SCSP, accessed October 31, 2025, https://www.scsp.ai/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Robotics-Memo.pdf